I started getting interested in the concept of Palestine/even the existence of the country and the people while i was taking History classes in high-school. That is European history class. Besides other points among the things that happened to lead to World War 2 was what Hitler was doing to Jews and among the things that happened when the war ended was the creation of Isreal, a Jewish state.

So, who are the Jews?

To understand the origin of the Jews (I am going to be using the Bible mostly as my point of reference and in some cases the Quran.

Let's go back to Abraham

Abraham is best known for his son Isaac and his role in the story of Sarah.

Abraham belonged to a group of ancient Semitic peoples. The term "Semitic" refers to a linguistic and ethnic family that includes ancient Hebrews, Arabs, Assyrians, and others from the Near East.

According to the Bible (Genesis 11:28–31), Abraham was born in Ur, a city in ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). This places his early cultural roots in a region influenced by Sumerian and Akkadian civilizations.

Abraham is first referred to as a “Hebrew” in Genesis 14:13. The term likely derives from Eber, one of his ancestors, and came to denote a distinct group of people who later became the Israelites.

Abraham gave birth to two sons; Isaac and Ishmael. Ishmael was the son of Hagar who was a servant at Abraham's house and had conceived for Abraham before Sarah. She was later thrown out of the house as Sarah contested her stay.

Ishmael

Ishmael was the first son of Abraham (Ibrahim in Islam). His mother was Hagar, an Egyptian servant of Sarah (Abraham’s wife).

Ishmael was born in Canaan, while Abraham and Sarah were living there. After Isaac was born, tensions arose, and Hagar and Ishmael were sent away.

They wandered in the wilderness of Beersheba (southern current Israel).

In the wilderness, God promised Hagar that Ishmael would not be abandoned and that he would become the father of a great nation.

Eventually, Ishmael settled in the wilderness of Paran, which is generally believed to be in the northern Sinai Peninsula or northwestern Arabia (modern-day Saudi Arabia region).

“Ishmael” (Yishma‘el) means “God hears”, reflecting the story where God heard Hagar’s cries when she fled into the wilderness.

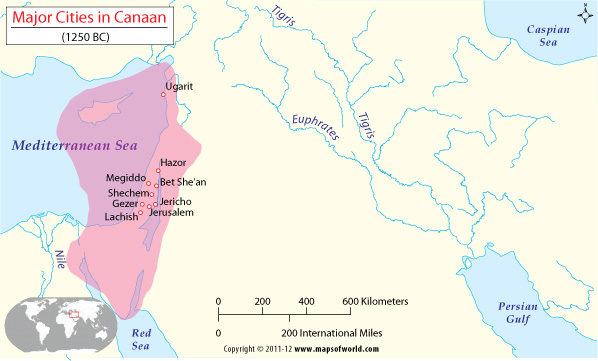

Historians and theologists believe that Canaan is the Promised Land of the Israelites referred to in the Old Testament. The book of Genesis refers to the Canaanites as descendants of Canaan.

References to the land of Canaan are also found in ancient Egyptian, Phoenician, and Syrian texts. In most of these, the land of Canaan seems to encompass parts of Syria, Jordan, and Israel, in addition to Palestine. The name Canaan is believed to have been derived from the Semitic word for purple. This could be a reference to the purple dye found aplenty in Palestine.

Genesis 25:12–18 lists Ishmael’s twelve sons, considered the founders of Arabian tribes:

- Nebaioth

- Kedar

- Adbeel

- Mibsam

- Mishma

- Dumah

- Massa

- Hadad

- Tema

- Jetur

- Naphish

- Kedemah

These became chiefs of tribes stretching across the Arabian desert, from the Red Sea to Mesopotamia.

Ishmael’s descendants gradually spread across the Arabian Peninsula, forming the core of the northern Arab tribes. Over.Over centuries, they intermixed with other Semitic peoples of the region. By the time of Islam (7th century CE), Ishmael was firmly understood as the ancestor of the Arabs, providing a genealogical link between Arabs and Abraham.

Palestinians are Arabs, and their identity emerged more recently (19th–20th century) in the specific land of Palestine. Through Arab lineage, they trace symbolic ancestry back to Ishmael, just as Jews trace theirs to Jacob (Israel).

This shared Abrahamic ancestry is why Jews and Arabs are often described as “cousins.”

Isaac

Isaac was born to Abraham and Sarah as a miraculous fulfillment of God’s promise. Sarah was 90 years old at the time (Genesis 21:1–3).

Isaac means “he laughs,” a reference to Sarah’s laughter when told she’d bear a child in old age (Genesis 18:12).

Isaac married Rebekah, whom Abraham’s servant found in Mesopotamia. Their love story is one of the gentler and more romantic episodes in Genesis (Genesis 24).

Isaac and Rebekah struggled with infertility, but after prayer, Rebekah conceived twins—Esau and Jacob (Genesis 25:21–26).

Isaac lived a long life—180 years. He favored Esau, while Rebekah favored Jacob, leading to family tension and the famous story of Jacob stealing Esau’s blessing (Genesis 27).

Jacob The younger twin. Known for his cunning and spiritual legacy. He was later renamed Israel and became the father of the twelve tribes of Israel.

Jacob

Jacob was the son of Isaac and Rebekah, and the grandson of Abraham and Sarah.

He had a twin brother, Esau, but unlike Esau (the elder twin), Jacob was more associated with quietness, domesticity, and faith in the God of his ancestors.

Jacob’s story is preserved in the Book of Genesis (chapters 25–50) in the Hebrew Bible.

Jacob’s name in Hebrew (Yaʿaqov) is often linked to “heel” or “supplanter,” because he was said to be born grasping Esau’s heel.

Through a famous story, Jacob (with his mother’s help) received Isaac’s blessing, which was intended for Esau. This set the stage for tension between the brothers.

To escape Esau’s anger, Jacob fled to his uncle Laban in Haran (Mesopotamia).

On the way, he had a vision known as “Jacob’s Ladder” — a staircase reaching heaven with angels ascending and descending. God reaffirmed to Jacob the covenant given to Abraham:

- His descendants would be numerous.

- They would inherit the land of Canaan.

- Through them, all nations would be blessed.

This confirmed Jacob as the chosen bearer of Israel’s covenantal identity.

Jacob married Leah and Rachel (sisters), and also had children with their maidservants Zilpah and Bilhah.

He fathered 12 sons and 1 daughter (Dinah). The sons became the ancestors of the 12 Tribes of Israel:

- Reuben

- Simeon

- Levi

- Judah

- Dan

- Naphtali

- Gad

- Asher

- Issachar

- Zebulun

- Joseph

- Benjamin

Each tribe would later form part of the Israelite confederation, with land allotments in Canaan (except Levi, who became the priestly tribe).

The turning point of Jacob’s life came when he wrestled all night with a mysterious being (described as a man, an angel, or even God Himself).At dawn, the being blessed Jacob and gave him a new name: “Israel”, meaning “He who struggles with God” or “God prevails.”

This name marked a transformation — Jacob was no longer just an individual, but the symbolic ancestor of an entire people defined by struggle, faith, and covenant.

The descendants of Jacob/Israel became known as the Children of Israel (Benei Yisrael).Over time, their descendants formed the Israelite nation.

The southern Kingdom of Judah (named after Jacob’s son Judah) survived longer than the northern Kingdom of Israel. From this tribe, the term “Jew” (from “Yehudi,” meaning “from Judah”) emerged.

Thus, Jacob is the ancestral patriarch of the Jewish people.

The origin of Palestine (the state)

I. Antiquity: From Geographical Term to Imperial Province

Land Markings and Identity

The name "Palestine" derives from the Greek Palaistinē, a term used by writers like Herodotus in the 5th century BCE to refer to the coastal region inhabited by the Philistines. For centuries, it remained a geographical descriptor rather than a formal administrative name. The area was known by various names, including Canaan and, later, the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah.

A pivotal moment occurred in 135 CE when the Roman Emperor Hadrian crushed the Bar Kokhba revolt. To suppress Jewish nationalism, he merged Roman Judaea with Galilee and renamed the consolidated province Syria Palaestina. This was the first time the name "Palestine" was officially applied to a large, unified administrative territory, marking a significant step in the formalization of its identity.

Ethnicities and Demographics

The ancient population was a Semitic mosaic. It included Canaanites, Israelites (Jews), Philistines, Samaritans, Edomites, and Phoenicians. During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the region saw an influx of Greeks, Romans, and other peoples from across the empire, creating a cosmopolitan society, particularly in newly founded cities like Caesarea Maritima. The Jewish population was the majority in Judaea and Galilee, with significant Samaritan communities in Samaria.

Social and Economic Changes

Society was predominantly agrarian, with life centered around the cultivation of wheat, olives, and grapes. The region's position as a land bridge between Egypt, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia made it a crucial corridor for trade. Roman rule brought significant infrastructure development, including roads and aqueducts, which spurred commerce but also imposed heavy taxation.

II. Byzantine and Early Islamic Eras: A Holy Land

Land Markings and Identity

The Byzantine Empire, upon inheriting the region, retained the name, dividing it into Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda, and Palaestina Salutaris (Tertia). Jerusalem's importance grew immensely as a center of Christian pilgrimage.

Following the Muslim conquest in the 7th century, the region's administrative identity was again preserved. The new rulers established Jund Filastin ("the military district of Palestine") as part of the larger province of Bilad al-Sham. Its capital was initially at Lydda and later moved to the newly founded city of Ramla. The boundaries of Jund Filastin largely corresponded to those of Palaestina Prima.

Ethnicities and Demographics

Under Byzantine rule, the region became majority Christian, though Jewish and Samaritan communities persisted. The population was primarily Aramaic-speaking. The Arab conquest initiated a gradual but profound shift. Over centuries, Arabization and Islamization took hold, with Arabic replacing Aramaic and Islam becoming the dominant religion. However, sizable and protected Christian and Jewish communities remained integral to the social fabric.

Social and Economic Changes

The economy was heavily influenced by the region's religious significance. Christian pilgrimage fueled a vibrant service economy. Under the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates, the focus shifted. The establishment of Ramla as the administrative center stimulated new trade patterns. Innovations in agriculture, including the introduction of new crops like citrus fruits and sugarcane, also occurred during this period.

III. The Ottoman Empire (1517–1917): A Mosaic of Districts

Land Markings and Identity

For 400 years, the Ottoman Empire ruled the region. Critically, there was no single administrative unit named "Palestine" during this time. The territory that would become modern Palestine was divided among several administrative districts (sanjaks), which were in turn part of larger provinces (vilayets), primarily the Vilayet of Syria and, later, the Vilayet of Beirut. In 1872, the Ottomans created the independent Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem, a special district under the direct authority of Istanbul due to its international significance. The term "Palestine" was used informally by educated Arabs and more formally by Western diplomats and pilgrims to refer to the Holy Land.

Ethnicities and Demographics

The population was overwhelmingly Arabic-speaking, the vast majority being Sunni Muslims. There were also significant Arab Christian communities (of various denominations) and smaller groups like the Druze. A centuries-old Jewish community (the Old Yishuv) was concentrated in the four holy cities: Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed, and Tiberias. The late 19th century marked the beginning of modern Zionist immigration (Aliyah) from Europe, which began a gradual shift in the demographic landscape.

Social and Economic Changes

The Ottoman era was characterized by a largely feudal, agrarian economy. In the latter half of the 19th century, Ottoman modernization reforms (Tanzimat) and growing European influence began to transform society. Infrastructure projects like the Jaffa-Jerusalem railway, the development of ports, and the introduction of modern legal and property systems integrated the region more deeply into the global economy. This period saw the rise of a new class of urban notables and merchants, particularly in cities like Jaffa, Haifa, and Jerusalem.

IV. The British Mandate (1920–1948): The Forging of a Modern Entity

Land Markings and Identity

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I was a watershed moment. The League of Nations granted Britain a mandate to govern the territory, creating the Mandate for Palestine. For the first time in centuries, Palestine became a single, unified political entity with defined borders. These borders, drawn by Britain and France, included the land west of the Jordan River. Transjordan (modern-day Jordan) was administratively separated in 1922. It was during this period that a modern, distinct Palestinian Arab national identity crystallized, largely in response to the Mandate's dual obligation to the Arab population and the Zionist project.

Ethnicities and Demographics

The Mandate period was defined by dramatic demographic change. Large-scale Jewish immigration, particularly from the 1930s, significantly increased the Jewish share of the population, from roughly 11% in 1922 to about 32% by 1947. This rapid shift created immense social and political friction, leading to recurring outbreaks of violence and the Arab Revolt of 1936–1939.

Social and Economic Changes

The Mandate saw rapid modernization and economic growth, but it was deeply uneven. The Jewish sector, benefiting from capital from abroad and a communal structure, developed a dynamic, semi-autonomous economy with new industries, agricultural settlements (kibbutzim), and institutions. The Arab economy also grew but was unable to keep pace. This economic disparity exacerbated political grievances and contributed to the growing divide between the two communities.

V. Post-1948: Partition and the Pursuit of Statehood

Land Markings and Identity

In 1947, the United Nations approved a Partition Plan (Resolution 181) to divide Mandate Palestine into independent Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem under international administration. The plan was accepted by Jewish leaders but rejected by Arab leaders. The ensuing 1948 Arab-Israeli War led to the establishment of the State of Israel. The remaining territories—the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip—came under Jordanian and Egyptian control, respectively.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza. The Palestinian identity, now inextricably linked to the experience of displacement and occupation, was politically channeled through the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). In 1988, in Algiers, the PLO formally declared the independence of the State of Palestine, defining its territory as the West Bank and Gaza with East Jerusalem as its capital.

The Oslo Accords of the 1990s created the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), granting it limited self-rule in parts of the occupied territories, which were divided into Areas A (full Palestinian civil and security control), B (Palestinian civil control, joint Israeli-Palestinian security control), and C (full Israeli civil and security control).

Ethnicities and Demographics

The 1948 war resulted in the displacement of over 750,000 Palestinians, creating a lasting refugee crisis. Today, the population of the West Bank and Gaza is almost entirely Palestinian Arab.

Social and Economic Changes

The economy of the Palestinian territories has been profoundly shaped by the ongoing conflict and occupation. Restrictions on movement, trade, and access to resources have severely hampered economic development, leading to high unemployment and dependence on international aid. The PNA has worked to build state institutions, but its economic and political sovereignty remains heavily constrained.

The origin of Isreal (the state)

I. Ancient Roots & Foundational Identity

Land Markings and Identity

The foundational identity of Israel is rooted in the ancient connection of the Jewish people to a specific territory, known in Jewish tradition as Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel). This connection is central to the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh), which narrates the story of the Israelite tribes, their covenant with God, and their settlement in the land. The establishment of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah around the 10th century BCE represents the first period of Jewish sovereignty in the region. Jerusalem, with its sacred Temple, became the undisputed religious and political center of Jewish life. Even after the destruction of the First Temple (586 BCE) and subsequent exiles, this land remained the focal point of Jewish identity and religious aspiration.

Ethnicities and Demographics

The population of the ancient kingdoms was primarily Israelite (Jewish). They lived alongside other Canaanite peoples and, over time, interacted with successive regional powers, including Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans, which led to some cultural and demographic intermingling.

Social and Economic Changes

The society was initially tribal and pastoral, evolving into a centralized monarchy with a largely agrarian economy. The cultivation of olives, grapes, dates, and wheat was central. The kingdom's strategic location along trade routes facilitated commerce. The construction of the Temple in Jerusalem established a powerful priestly class and a centralized system of religious and legal authority that structured social life.

II. The Rise of Modern Zionism (19th Century)

Land Markings and Identity

For nearly two millennia, the Jewish people lived in diaspora, scattered across the globe. While the religious connection to Zion remained a core tenet of Judaism, a modern political movement to re-establish a Jewish homeland only emerged in the late 19th century. Political Zionism, articulated by thinkers like Theodor Herzl, was a direct response to the persistent antisemitism in Europe and the rise of modern nationalism. Herzl's 1896 pamphlet, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State), argued that the only solution to the "Jewish Question" was the creation of a sovereign, internationally recognized Jewish state. The movement sought to transform a religious and cultural identity into a modern national and political one, focused on returning to the ancestral land.

Ethnicities and Demographics

During this period, the Jewish people were a global diaspora with distinct cultural subgroups (e.g., Ashkenazi from Central/Eastern Europe, Sephardi from the Iberian Peninsula/North Africa). The first waves of organized immigration to Ottoman Palestine, known as the First and Second Aliyah (1882-1914), began to establish a small but ideologically driven Jewish community (Yishuv) in the land. This community was a tiny minority within the predominantly Arab population.

Social and Economic Changes

The early Zionist immigrants were motivated by an ideology of "redeeming the land" through manual labor. They established new agricultural settlements, most notably the kibbutz (collective farm) and the moshav (cooperative farm). These settlements were not just economic enterprises but also social experiments aimed at creating a "New Jew" — secular, socialist, and tied to the soil. This period also saw the revival of Hebrew as a modern spoken language, a crucial element in forging a new national culture.

III. The British Mandate & Nation-Building (1920–1948)

Land Markings and Identity

The British Mandate for Palestine, established after World War I, was the crucible in which the State of Israel was forged. The 1917 Balfour Declaration, incorporated into the Mandate, pledged British support for the "establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people." This provided the political and legal framework for the Zionist movement to build the institutions of a state-in-waiting. The Yishuv developed its own political body (the Jewish Agency), trade union (the Histadrut), and paramilitary defense force (the Haganah). This period of state-building occurred in parallel with, and often in conflict against, the rise of a distinct Palestinian Arab national movement.

Ethnicities and Demographics

This era was defined by successive waves of Jewish immigration (Aliyah), dramatically altering the demographic balance. Fleeing persecution in Europe, particularly the rise of Nazism, Jewish immigrants arrived in large numbers. The Jewish population grew from about 85,000 (11%) in 1922 to approximately 630,000 (32%) by 1947. This rapid influx created intense friction with the Arab majority, leading to escalating violence.

Social and Economic Changes

The Yishuv developed a robust and semi-autonomous economy. Capital from abroad was invested in agriculture, industry, and construction. New cities like Tel Aviv grew rapidly, and institutions like the Hebrew University and the Technion were founded. The economy was largely separate from the Arab economy, with distinct labor markets, agricultural sectors, and commercial networks, creating a dual society within the Mandate.

IV. Independence and the Early State (1948–1967)

Land Markings and Identity

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations voted to partition Mandate Palestine into independent Arab and Jewish states. The Jewish leadership accepted the plan, and on May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of the State of Israel. The declaration was immediately followed by an invasion by neighboring Arab states, initiating the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (or War of Independence). The armistice lines established in 1949, known as the Green Line, served as Israel's de facto borders until 1967. The central identity of the new state was defined as Jewish and democratic, with a mission to be a haven for Jewish people from around the world.

Ethnicities and Demographics

The war created a profound demographic shift. Around 750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled, becoming refugees. Concurrently, Israel absorbed two massive waves of Jewish immigrants: Holocaust survivors from Europe and, in even greater numbers, Jews fleeing persecution in Arab countries (Mizrahi Jews). This influx doubled Israel's Jewish population within its first three years. This created a new social dynamic, with a culturally European Ashkenazi elite and a large, often marginalized, Mizrahi population. The approximately 150,000 Arabs who remained within Israel's borders became citizens.

Social and Economic Changes

The early years were marked by severe economic austerity (Tzena). The state focused on building a centralized, socialist-inspired economy to absorb the massive immigration. Housing was scarce, leading to the creation of temporary transit camps (ma'abarot). The government invested heavily in national infrastructure projects, a unified school system, and a strong military (the Israel Defense Forces, or IDF), which became a crucial institution for social integration.

V. Post-1967: Expansion, Conflict, and more conflict

Land Markings and Identity

The Six-Day War in 1967 was a transformative event. Israel captured the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan, the Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, and the Golan Heights from Syria. This victory fundamentally altered Israel's strategic position and its national identity. The Green Line was blurred as Israel took control of territories inhabited by over a million Palestinians. The "Land of Israel" was now largely under Jewish control, igniting a fervent debate within Israeli society about the nation's character, borders, and destiny. This led to the rise of the settlement movement, which sought to establish a permanent Jewish presence in the newly occupied territories.

Ethnicities and Demographics

The control over the West Bank and Gaza placed a large Palestinian population under Israeli military rule, creating the enduring reality of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The demographic balance between Jews and Arabs within the territories controlled by Israel became a central political issue. The Israeli population itself became more diverse, with significant immigration from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s and from Ethiopia.

In the 1990s, Israel saw significant immigration from Ethiopia primarily due to the airlift operations that brought Ethiopian Jews, known as Beta Israel, to the country. Two major operations, Operation Solomon in 1991 and earlier Operation Moses in 1984-1985, facilitated this migration.

The Beta Israel community, recognized as Jews by Israel, faced persecution, famine, and political instability in Ethiopia, particularly during the civil war and under the Marxist Derg regime. Israel's Law of Return, which grants Jews worldwide the right to immigrate, extended to Ethiopian Jews after rabbinical authorities confirmed their Jewish status in the 1970s.

This was the peak of the immigration wave in the 1990s. Over a 36-hour period on May 24-25, 1991, Israel airlifted 14,325 Ethiopian Jews to Israel. The operation was prompted by the deteriorating situation in Ethiopia, where rebels were advancing on Addis Ababa, endangering the Jewish community. Israel, with U.S. support, negotiated their safe exit.

Ethiopian Jews faced religious discrimination, economic hardship, and violence. The famine in the 1980s and ongoing civil war made life untenable, pushing many to seek refuge in Israel, where they could practice their faith freely and access better opportunities.

Israel actively worked to integrate Ethiopian Jews, viewing their immigration as part of its mission to gather Jewish diaspora communities. The government provided support for resettlement, though integration challenges persisted.

Ethiopian Jews in Sudan (en route to Israel) and those already in Israel advocated for family reunification, pressuring the Israeli government to expedite immigration for those left behind after earlier operations.

By 1999, over 30,000 Ethiopian Jews had immigrated to Israel, with the majority arriving in the early 1990s.

Social and Economic Changes

Beginning in the 1980s, Israel's economy underwent a dramatic transformation from a centralized, state-led model to a free-market, high-tech powerhouse. Dubbed "Silicon Wadi," Israel became a global leader in innovation, cybersecurity, and startups. This economic boom created immense wealth but also increased social inequality. Simultaneously, Israeli society has faced deep internal divisions: between religious and secular Jews, between the Ashkenazi and Mizrahi communities, and over the political and moral questions surrounding the ongoing occupation and the conflict with the Palestinians. Peace treaties with Egypt (1979) and Jordan (1994) secured key borders, but the core conflict remains unresolved.

Whose land is it for then?

I. The Genesis of Conflict:

Two Peoples, One Land (Late 19th Century – 1947)

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not, in its essence, an ancient religious war. It is a modern national conflict born in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, centered on the competing claims of two national movements to the same piece of territory.

Why and When It Started

The conflict's origins can be traced to the simultaneous emergence of two distinct nationalisms:

Jewish Nationalism (Zionism):

In response to centuries of persecution and the rise of modern, racial antisemitism in Europe, Jewish intellectuals and leaders developed political Zionism. The movement's central tenet, articulated by figures like Theodor Herzl, was that the only viable solution to the "Jewish Question" was the re-establishment of a sovereign Jewish homeland in their ancestral Land of Israel (known as Palestine). This was both a political project and the fulfillment of a 2,000-year-old religious and cultural connection to the land, known as Zion.

Palestinian Arab Nationalism:

Concurrently, the Arab inhabitants of the Ottoman province of Syria, including Palestine, were developing their own national consciousness. This movement, part of a broader Arab awakening, sought independence from the Ottoman Empire and, later, from European colonial rule. For Palestinian Arabs, the land was their home, where they had lived for centuries as the overwhelming majority, and they aspired to self-determination and the creation of their own independent state.

The collision of these two movements was inevitable, as both laid claim to the same territory. The situation was critically inflamed by the Balfour Declaration of 1917, in which Great Britain, the emerging mandatory power, promised to support the "establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people," while also stating that "nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine." These dual, and ultimately irreconcilable, promises set the stage for a zero-sum conflict.

II. The Major Wars:

From State-vs-State to Asymmetric Conflict

The evolution of the conflict can be understood through its major military confrontations, which have shifted from conventional wars between states to protracted, asymmetric conflicts between Israel and non-state actors.

1. The 1948 Arab-Israeli War (Israel's "War of Independence" / Palestine's "Nakba")

Following World War II and the Holocaust, international support for a Jewish state grew. In 1947, the United Nations passed Resolution 181, recommending the partition of Mandate Palestine into independent Jewish and Arab states. Jewish leaders accepted the plan; Arab leaders and states rejected it, arguing it was unjust to the Arab majority.

The War:

On May 14, 1948, as the British Mandate expired, David Ben-Gurion declared the independence of the State of Israel. The next day, the armies of Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq invaded. The war was fought in two phases, separated by a brief truce. The newly formed and highly motivated Israel Defense Forces (IDF) managed to halt the Arab advance and eventually gain the offensive.

Outcome & Consequences:

Israel won a decisive military victory. The 1949 Armistice Agreements established de facto borders (the "Green Line") that gave Israel control over 78% of Mandate Palestine, significantly more than the UN plan had allotted. The remaining territories, the West Bank and Gaza Strip, were occupied by Jordan and Egypt, respectively. For Palestinians, the war was the Nakba ("Catastrophe"): an estimated 750,000 people fled or were expelled from their homes, creating a Palestinian refugee crisis that remains unresolved to this day.

2. The 1967 Six-Day War (The "Naksa")

Tensions escalated dramatically in mid-1967. Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser blockaded the Straits of Tiran (Israel's southern maritime outlet), expelled UN peacekeepers from the Sinai, and signed mutual defense pacts with Jordan and Syria, encircling Israel.

The War:

Believing a coordinated Arab attack was imminent, Israel launched a preemptive strike on June 5, 1967. In a stunningly successful air campaign, it destroyed the bulk of the Egyptian air force on the ground within hours. Over the next five days, the IDF defeated the armies of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria.

Outcome & Consequences:

The war was a transformative event. Israel captured the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria. This began Israel's military occupation of the Palestinian territories. For Palestinians, this was the Naksa ("Setback"), bringing the entire Palestinian population of Mandate Palestine under Israeli control. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 242, establishing the "land for peace" formula that would become the cornerstone of future peace negotiations.

3. The 1973 Yom Kippur War (The October War)

Following the humiliation of 1967, Egypt and Syria, under Anwar Sadat and Hafez al-Assad, planned to reclaim their lost territories.

The War:

On October 6, 1973—Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism—Egypt and Syria launched a coordinated surprise attack. Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal and overran the Israeli Bar-Lev Line, while Syrian troops advanced on the Golan Heights. Israel was caught completely unprepared and suffered heavy initial casualties.

Outcome & Consequences:

After initial setbacks, the IDF regrouped, repelled both invasions, and even pushed into Syrian and Egyptian territory before a US-brokered ceasefire took hold. While a military defeat for the Arab states, the war was a political and psychological victory. It shattered the myth of Israeli invincibility and restored Arab pride, making diplomacy possible. This war directly paved the way for the Camp David Accords (1978) and the 1979 Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty, where Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt in exchange for full diplomatic recognition—the first such treaty between Israel and an Arab nation.

4. The Intifadas: The Shift to Asymmetric Warfare

By the 1980s, the conflict's center of gravity had shifted from state-vs-state warfare to the struggle between Israel and Palestinians living under occupation.

The First Intifada (1987–1993):

A spontaneous, grassroots Palestinian uprising began in the Gaza Strip and quickly spread to the West Bank. It was characterized by civil disobedience, mass protests, strikes, and low-level violence like stone-throwing. The televised images of Israeli soldiers confronting young Palestinians shifted global perceptions. The Intifada's political pressure was instrumental in leading to the 1993 Oslo Accords, which created the Palestinian Authority (PA) and a framework for a two-state solution that ultimately failed.

The Second Intifada (2000–2005):

Following the collapse of the Camp David II peace summit, a far more violent uprising erupted. It was characterized by widespread armed attacks and, most devastatingly, a campaign of suicide bombings by Palestinian militant groups like Hamas against Israeli civilians. Israel responded with major military operations, including incursions into Palestinian cities and targeted assassinations. The violence led Israel to construct the controversial West Bank Barrier and, in 2005, to unilaterally disengage its settlements and forces from the Gaza Strip.

5. Recent Conflicts: Wars with Hamas and Hezbollah

Since the Second Intifada, the conflict has been defined by clashes with powerful non-state actors.

2006 Second Lebanon War:

A 34-day conflict between Israel and Hezbollah, triggered by a cross-border raid. Hezbollah launched thousands of rockets at northern Israeli cities, and Israel conducted a massive air and ground campaign in southern Lebanon.

The Gaza Wars (2008-09, 2012, 2014, 2021, 2023–Present):

After Hamas seized control of Gaza in 2007, a cycle of conflict emerged. These wars are typically ignited by escalating tensions and rocket fire from Gaza into Israel, followed by large-scale Israeli military operations. These are highly asymmetric conflicts, fought in one of the world's most densely populated areas, resulting in devastating humanitarian consequences for Palestinian civilians in Gaza. The most recent and destructive of these began in October 2023 after a major Hamas attack on southern Israel.

The Holocaust

Origins

The Holocaust, known in Hebrew as the Shoah or "Catastrophe," stands as one of the most harrowing chapters in human history: the systematic, state-sponsored genocide orchestrated by Nazi Germany and its collaborators, resulting in the murder of approximately six million Jews*—roughly two-thirds of Europe's Jewish population—along with millions of others deemed undesirable, including Roma, disabled individuals, political dissidents, and Soviet prisoners of war. This atrocity unfolded primarily between 1941 and 1945, though its roots extended back to the early 1930s, embedded in a toxic brew of ideological fanaticism, economic turmoil, and entrenched prejudice. To comprehend this genocide requires examining its origins and causes, the mechanisms of its implementation, the profound indifference of the international community that allowed it to persist unchecked for years, and the confluence of events that finally brought it to a halt with the Allied victory in World War II.

The origins of the Holocaust can be traced to deep-seated antisemitism that permeated European society for centuries, evolving from religious animosity—rooted in medieval Christian doctrines accusing Jews of deicide—to modern racial pseudoscience that portrayed Jews as an inherent biological threat. In Germany, this prejudice intensified in the aftermath of World War I, where the humiliating Treaty of Versailles imposed crippling reparations, territorial losses, and military restrictions, fostering a national sense of victimhood and resentment. The economic devastation of the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s exacerbated these grievances, creating fertile ground for extremist ideologies. Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazis) capitalized on this chaos, rising to power in January 1933 through a combination of legal maneuvering, propaganda, and violence. Hitler's worldview, articulated in his 1925 manifesto Mein Kampf, framed Jews not merely as outsiders but as a parasitic "racial enemy" undermining Aryan supremacy, necessitating their elimination to secure Lebensraum (living space) for the German Volk.

The causes were multifaceted, blending ideological zeal with pragmatic opportunism. At the core was Nazi racial ideology, which dehumanized Jews as Untermenschen (subhumans), justifying their persecution as a defensive act against an imagined existential threat.

Social-psychological factors played a pivotal role: fear of reprisal under the Nazi police state discouraged dissent, while material gain—through the plunder of Jewish property—enticed participation from ordinary citizens and collaborators across occupied Europe.

Deference to authority, reinforced by hierarchical structures in German society and indoctrination via institutions like the Hitler Youth, further normalized complicity.

Economic motivations intertwined with ideology; the Nazis' early policies aimed at "Aryanization," forcibly transferring Jewish businesses to non-Jews, which appealed to those seeking personal enrichment amid widespread poverty. These elements coalesced into a escalating campaign: beginning with boycotts of Jewish businesses in April 1933, the dismissal of Jews from civil service, and the infamous book burnings in May 1933, progressing to the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 that stripped Jews of citizenship and prohibited intermarriage, and culminating in the pogrom of Kristallnacht in November 1938, which destroyed synagogues and businesses while arresting thousands.

As the Nazis expanded their reach with the invasion of Poland in September 1939—igniting World War II—the persecution morphed into genocide. Jews were herded into overcrowded ghettos in occupied territories, subjected to starvation and disease. The 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union marked a turning point, with mobile killing squads (Einsatzgruppen) executing over a million Jews and others in mass shootings. By early 1942, the Wannsee Conference formalized the "Final Solution," coordinating the deportation of Jews to extermination camps like Auschwitz-Birkenau, Treblinka, and Sobibor, where industrial-scale murder via gas chambers and crematoria claimed the majority of victims, peaking in 1942. The Holocaust's machinery relied on a "bundled motivations" framework: extreme antisemitism among Nazi elites combined with utilitarian incentives for broader society, ensuring widespread collaboration.

Tragically, the world largely ignored the unfolding horror for the duration of its occurrence, from the early persecutions in the 1930s through the height of the genocide in the 1940s, due to a confluence of isolationism, antisemitism, bureaucratic inertia, and wartime priorities. In the prewar years, as tens of thousands of Jews fled Germany—approximately 282,000 from Germany and 117,000 from Austria by September 1939—receiving nations imposed stringent barriers. The United States, for instance, maintained a quota of about 27,370 immigrants from Germany annually, admitting only 2,372 German Jews in 1933 amid additional visa hurdles. The Evian Conference of July 1938, convened by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to address the refugee crisis, ended in failure; no country expanded quotas or offered substantive aid, effectively signaling to the Nazis that the international community would not intervene. Nazi policies like the "Flight Tax" further impeded emigration, trapping the economically vulnerable.

During the war, Allied governments possessed fragmentary but credible intelligence about the atrocities, including reports from Polish exiles and escaped prisoners, yet dismissed much as exaggerated propaganda until late 1942. A December 1942 pamphlet by the Polish government-in-exile detailed mass murders, prompting the Bermuda Conference in April 1943, but this too yielded no rescue plans, with Allies insisting that military victory was the sole path to relief—a stance that condemned millions to death between 1943 and 1945. Factors such as domestic antisemitism, fear of espionage, and reluctance to divert resources from the war effort underpinned this inaction; even the Vatican under Pope Pius XII, while aiding some individuals, refrained from public condemnation.

Cotton Candy Skies

The State of Israel was proclaimed on May 14, 1948, amid the ashes of World War II and the horrors of the Holocaust, which had claimed the lives of six million Jews and millions of others. For many Zionists, Israel represented a sanctuary from centuries of persecution. However, this birth was inextricably linked to what Palestinians term the Nakba (Arabic for "catastrophe"), a period of mass displacement and violence that set the tone for decades of conflict.

In the lead-up to and following Israel's declaration of independence, approximately 700,000 Palestinians—over half the Arab population of Mandate Palestine—were expelled or fled their homes. Israeli forces, including paramilitary groups like the Haganah and Irgun, conducted operations that razed over 500 Palestinian villages. Declassified Israeli archives reveal instances of deliberate brutality, such as the Deir Yassin massacre in April 1948, where over 100 villagers, including women and children, were killed by Irgun and Lehi fighters. This was not an isolated incident; similar events occurred in Lydda (Lod), where thousands were forcibly expelled under threat of bombardment, and in Tantura, where recent scholarship has uncovered evidence of mass executions.

These actions were justified by Israeli leaders as necessary for securing a Jewish-majority state amid Arab hostilities, but they resulted in profound demographic engineering. Palestinians were often denied the right of return, their properties confiscated under laws like the Absentee Property Law of 1950. This foundational violence established a pattern: state policies that prioritized territorial control and security at the expense of Palestinian rights, leading to cycles of resistance, repression, and escalation.

Escalation Through Occupation and Conflict: A Chronicle of Brutality

The brutality intensified with the 1967 Six-Day War, during which Israel captured the West Bank, Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, and other territories. This occupation, now over half a century old, has been marked by systematic measures that human rights organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch describe as apartheid-like in their discriminatory impact. Settlements expanded illegally under international law, displacing Palestinians and fragmenting their lands. By 2023, over 700,000 Israeli settlers lived in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, often protected by military forces that enforced evictions and demolitions.

Key episodes underscore the human toll. The First Intifada (1987–1993) saw Israeli forces respond to Palestinian protests with live ammunition, beatings, and curfews, resulting in over 1,000 Palestinian deaths. The Second Intifada (2000–2005) was deadlier, with suicide bombings met by Israeli military operations like Operation Defensive Shield, which devastated Jenin refugee camp and killed hundreds. In Gaza, blockades since 2007—imposed after Hamas's election—have created what the UN has called an "open-air prison," with periodic wars (2008–2009, 2012, 2014, 2021, and the ongoing 2023–present conflict) leading to disproportionate casualties.

Statistics paint a grim picture: Since 2000 alone, over 10,000 Palestinians have been killed in conflicts with Israeli forces, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, with civilians comprising a significant portion. In the 2014 Gaza War, for instance, over 2,200 Palestinians died, including 500 children, amid intense aerial bombardments. The current Gaza conflict, triggered by Hamas's October 7, 2023, attack that killed 1,200* Israelis, has seen Palestinian deaths exceed 40,000 by mid-2025, with widespread destruction of infrastructure, including hospitals and schools. Reports from bodies like the International Court of Justice highlight allegations of collective punishment, echoing patterns of dehumanization.

This is not to absolve Palestinian militant groups of their own atrocities, such as rocket attacks and terrorism, which have claimed thousands of Israeli lives. Yet, the asymmetry of power—Israel's advanced military versus fragmented Palestinian resistance—has amplified the brutality's impact on civilians.

Parallels to the Holocaust: Ignorance, Indifference, and Belated Recognition

To draw a parallel, we must turn to the Holocaust (1933–1945), the systematic extermination of Jews by Nazi Germany. Early signs of persecution—such as the 1935 Nuremberg Laws stripping Jews of citizenship—were largely ignored by the international community. Reports of Kristallnacht (1938) and initial deportations reached Western governments, yet responses were tepid. The U.S. and Britain restricted Jewish immigration, as seen in the 1939 voyage of the MS St. Louis, where refugees were turned away. Even as intelligence confirmed death camps by 1942, Allied leaders prioritized military victory over targeted rescues, allowing the genocide to claim millions.

The world "ignored" the Holocaust not through total unawareness but through willful inaction, influenced by antisemitism, isolationism, and wartime priorities. Only after liberation in 1945, with graphic evidence from camps like Auschwitz, did global horror crystallize, leading to the Nuremberg Trials and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Similarly, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has unfolded under global scrutiny yet with persistent neglect. Despite UN resolutions condemning occupations and settlements, enforcement has been inconsistent. Major powers, including the U.S., provide Israel with military aid exceeding $3 billion annually, often vetoing critical Security Council measures. Media coverage, while extensive, frequently frames Palestinian suffering as collateral to Israeli security needs, diluting outrage.

I didn’t realize how heavy it was until i set it down

Here lies the crux: Palestinian deaths, though numbering in the tens of thousands since 1948, lack a "collective face"—a singular, emblematic narrative that humanizes the scale of loss. Unlike the Holocaust, immortalized through Anne Frank's diary or Schindler's List, or Rwanda's genocide with its machete-wielding imagery, Palestinian atrocities are diffuse: a child killed in a drone strike here, a family evicted there, a hospital bombed elsewhere. This fragmentation, compounded by competing narratives and accusations of bias, allows neglect to persist.

Social media has amplified voices, as seen in viral images from Gaza, yet algorithmic biases and geopolitical alliances often suppress them. The result? A tragedy that simmers without boiling over into transformative intervention, much like the Holocaust's early years. The world "realizes" in fits and starts—through ICJ rulings or BDS movements—but sustained action lags, perpetuating the cycle.

In documenting Israel's brutality toward Palestinians since 1948, we see not a monolithic evil but a tragic interplay of nationalism, fear, and power imbalances. Relating this to the Holocaust underscores a universal failing: humanity's capacity for indifference until atrocities become undeniable. For Palestinians, the absence of a collective face sustains this neglect, but history teaches that recognition can come—albeit late. As players and citizens of the world as a piece, we must advocate for truth, accountability, and dialogue, lest we repeat the sins of inaction. Peace demands acknowledging all suffering, Israeli and Palestinian alike, to forge a shared future.