Humans have long exchanged their time a commodity they can't touch for various things, including money (jobs), love (relationships), power (leadership), sex (prostitution), hope (education), and countless other things, some of which are hard to even describe.

The question, "Am I behind in life?" is a modern malady. It whispers in our ear at a friend's wedding, shouts at us during a job search, and haunts us during quiet moments of reflection. We feel it as a profound and personal failure. But what if this feeling isn't a reflection of our inadequacy, but rather a symptom of a very specific, and surprisingly recent, understanding of time itself?

Our popular culture is saturated with this temporal anxiety, constantly questioning the nature of the timeline we take for granted. In Christopher Nolan's Tenet, time is a malleable river that can be inverted, its flow reversed. The characters don't just move through time; they weaponize their directionality.

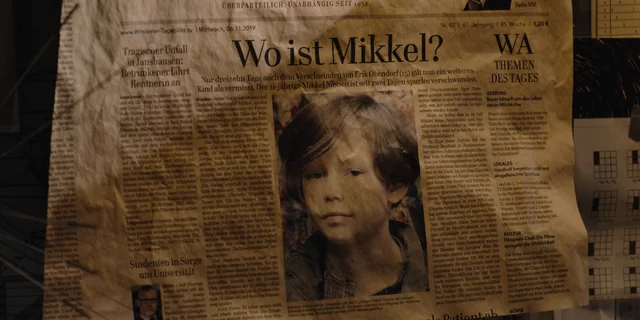

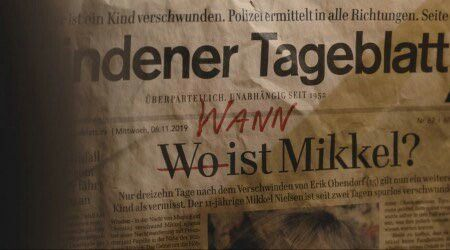

I recently watched The German series Dark which presents a more deterministic and terrifying vision: a closed loop where past, present, and future are inextricably knotted, and every action is not a choice but an echo whereas in the series Silo, history is erased and time becomes a suffocating, controlled cycle, where progress is forbidden.

These narratives, while fictional, expose a deep truth: our perception of time as a single, unbending, forward-marching arrow is just one story we tell ourselves. The anxiety of "being behind" only exists if we believe there is a single, correct timeline to be on.

The Historical Tapestry of Time

Before we could feel "behind," we had to invent the very line we're measuring ourselves against. For most of human history, time wasn't a road stretching to the horizon; it was a circle.

The Time Before Clocks

Animals don't worry about being behind schedule. A bear hibernates not because its calendar says it's November, but because of a deep, biological imperative tied to light, temperature, and food scarcity. This is event-based time. For early humans, time was not an abstract quantity but a sequence of natural events: the sun rises, we hunt; the sun sets, we rest; the rains come, we plant; the herds migrate, we follow. Time was measured in seasons, moons, and generational cycles—a repeating rhythm of existence. The core concept was kairos (the opportune moment) not chronos (quantitative, sequential time).

Animals possess their own sense of time, guided by biological clocks or circadian rhythms, which regulate behaviors across species from insects to mammals. These rhythms align activities with environmental factors like light and temperature. For instance, blind cave fish maintain functional internal clocks despite living without day-night cycles, showcasing an evolutionary adaptation for predicting time. Similarly, dogs experience time through routines and sensory cues, and their faster "hertz" rate—around 80 cycles per second compared to humans' 60—might make time feel slower for them.

The Human Time

Humanity's quest to measure time predates written history, emerging from the practical imperatives of agriculture, navigation, and ritual. Archaeological evidence suggests that as early as 5,000 years ago, the Babylonians and Egyptians began quantifying the day using rudimentary devices.

For the Ancient Egyptians, the most important clock was the Nile River. Its annual flood, recession, and the subsequent planting and harvest seasons dictated life, religion, and governance. Time was a reliable, repeating gift from the gods.

The Maya developed one of the most complex calendrical systems ever, conceiving of time in vast, nested cycles. Their Long Count calendar, which famously ended a cycle in 2012, didn't predict an apocalypse but simply the end of one world age and the beginning of another, much like an odometer rolling over.

The Babylonians, operating in a sexagesimal (base-60) numerical system, profoundly influenced modern timekeeping by partitioning the day into 24 hours—12 for day and 12 for night—and further subdividing hours into 60 minutes and minutes into 60 seconds. This system, refined by the Mesopotamians around 2,400 BCE, integrated time with spatial measurements, laying the groundwork for our contemporary units. Other cultures contributed uniquely: the Mayans developed intricate calendars based on interlocking cycles, while indigenous groups like the Australian Aboriginals conceptualized time through Dreamtime narratives, blending past, present, and future in a non-linear continuum. For Africa on the other side, some scholars wrote about African time only being the present and never the future. The way different cultures worked with/understood time as a concept kept adding more and more complexity to it to the point that this blog was written on Tuesday, Nehasa 27, 2017 (Ethiopian Time and Date).

Linear Paths and Eternal Cycles

Abrahamic religions brought forth a powerful linear narrative of time, marked by a definitive beginning (Creation), a pivotal event (the life of Christ), and a dramatic conclusion (the Last Judgment). Instead of a circular cycle, history becomes a divine story moving toward a final resolution, giving each individual life a unique, non-repeatable path within God's larger plan.

Religions have long assigned metaphysical meaning to time, offering varied perspectives on existence. In Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—time flows in a straight line, from creation to judgment, highlighting themes of progress, redemption, and eschatology. The Bible depicts as governed by God, with events like the miracle in Isaiah 38:8 showcasing divine control over its course. This linear view promotes individualism and a sense of historical purpose, standing in sharp contrast to the cyclical perspectives found in Eastern philosophies.

Hinduism and Buddhism, conversely, envision time as kalachakra—an endless wheel of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara), where epochs repeat until enlightenment breaks the cycle. Indigenous African and Native American cosmologies often blend these, perceiving time as rhythmic and relational, tied to natural cycles (seasons connected with harvest and planting) rather than rigid progression. Such perspectives challenge Western notions of "being behind," as cyclical time implies recurrence and renewal over linear achievement.

Philosophically, the origin of time has perplexed thinkers from antiquity. Aristotle viewed time as a measure of change, dependent on motion and thus not independent of events. Newton posited absolute time as an eternal container, flowing uniformly irrespective of the universe's contents. Leibniz countered that time is relational, emerging from interactions among entities. These debates echo in modern inquiries: Where did time "come from"? Scientifically, it originates with the Big Bang, approximately 13.8 billion years ago, as spacetime expanded from a singularity. Yet, quantum gravity theories suggest time might be emergent, arising from deeper, timeless structures.

In the past, time was such a confusing concept that in October 1582, 10 days vanished from the calendar due to the transition from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar. Specifically, the calendar jumped straight from October 4 to October 15.

The deeper you delve into the concept of time the more perplexing it becomes. Yet, for anyone studying it, that's the sweet spot—where the berry is darker, and the juice is sweeter.

Conventions and Conventions

The first mechanical clocks, created in medieval European monasteries, weren’t designed for commerce but for spiritual discipline, ensuring monks attended the seven daily prayers on time. These clocks introduced a groundbreaking concept: time could be separated from natural events and divided into equal, measurable units.

This new "clock time" became the backbone of the Industrial Revolution. Factories needed synchronized labor, and railways required standardized schedules to prevent accidents. The phrase "time is money" took hold, and time was no longer simply experienced—it was spent. This led to the establishment of global time zones and a universal industrial clock that dictates our lives today, from work hours to school routines.

Now, we follow the Gregorian, introduced in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII to improve the Julian system and align with solar years, including leap years for accuracy. This standardization, driven by religious and navigational demands, reflected a global agreement shaped by colonial expansions and industrial revolutions. The 24-hour day endures due to Egyptian and Babylonian contributions: Egyptians divided day and night into 12 hours each, while Babylonians' base-60 system gave us minutes and seconds. The 19th-century railways brought time zones, culminating in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), maintained by atomic clocks with occasional leap seconds to align with Earth's rotation.

Cultural differences added complexity: Monochronic societies, like Germany and the USA, see time as linear and segmented, emphasizing schedules and punctuality. In contrast, polychronic cultures, such as those in Latin America and the Middle East, view time as fluid, prioritizing relationships over rigid timelines, favoring multitasking and flexibility. These contrasting views underscore time’s social construction and its impact on everything from business practices to personal stress levels.

Time as We Know It Today

We now live entirely inside the architecture of industrial, linear time. And this architecture has built a psychological cage: the social clock.

The Unwritten Schedule

The "social clock" is the culturally inherited timetable that dictates the "right time" to accomplish major life milestones: graduate, get a job, buy a house, get married, have children, retire. This schedule is a 20th-century invention, a byproduct of a stable, industrial-era economy that created a predictable life path.

Today, social media acts as a powerful enforcement mechanism for this clock. It presents a curated, relentless stream of others seemingly hitting their marks precisely "on time," amplifying feelings of inadequacy and temporal anxiety. We are constantly comparing our unique, messy, and unpredictable journey to a fictional, standardized timeline.

Is Time Even Real?

While society was busy synchronizing its clocks, physics was discovering that time is far stranger than we could have imagined.

Newton's Absolute Time

For centuries, the commonsense view was the Newtonian one: time is an absolute, universal river flowing at the same rate for every observer in the universe. This is the time of our daily experience.

Einstein's Revolution

Albert Einstein's theories of relativity shattered this notion (Newton's). He proved that time is not absolute. It is relative to the observer's speed and the strength of the gravitational field. An astronaut on a fast-moving spaceship literally ages more slowly than someone on Earth (a phenomenon called time dilation). Clocks on GPS satellites have to be constantly adjusted to account for the fact that time moves faster for them in orbit. Time and space are woven together into a single fabric—spacetime—which can be warped and stretched. There is no universal "now."

The Arrow of Time

So why does time seem to move only forward? The most accepted scientific explanation is the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This law states that the total entropy (a measure of disorder or randomness) in an isolated system can only increase over time. A broken egg will never spontaneously reassemble itself. The universe moves from a state of order (the Big Bang) towards a state of maximum disorder. Our perception of time's "arrow" may simply be our observation of this inexorable march towards chaos.

For Watchers of “The Clock,” Time Is Running Out

So, let's return to our original, agonizing question: Am I behind in life?

Based on our journey, the answer is a definitive and liberating no. You cannot be behind in a race that does not exist.

The very question is built upon a stack of flawed premises. It assumes:

- There is one single timeline (Physics shows this is false; time is relative).

- This timeline is linear and forward-moving (History shows this is a recent, culturally specific idea, not a human universal).

- There are correct milestones to be hit at specific times (Sociology shows this "social clock" is a modern construct, not a natural law).

The feeling of being "behind" is a form of cultural jet lag. Our inner, biological, and psychological rhythms—which are cyclical and fluid—are in conflict with the rigid, mechanical, linear clock of post-industrial society.

The solution isn’t about running faster or trying to "catch up" on some imaginary track. It’s about stepping off the track entirely. It means consciously rejecting the tyranny of chronos and embracing the wisdom of kairos. Instead of asking, "What time is it?" we should be asking, "What is this time for?" In the series Dark, finding Mikkel wasn’t about asking "Wo ist Mikkel?" (Where is Mikkel?) but rather "Wann ist Mikkel?" (When is Mikkel?) to truly understand where he was in time.

You are probably behind on one clock and ahead on another.

You are exactly where you are, in your own time. The real task is not to catch up to an external schedule but to synchronize with yourself. To learn your own seasons, to honor your own rhythms, and to live a life that is measured not by the ticking of a clock, but by the richness of its moments. The real question is not "Am I behind in life?" but rather, "Where am I fully in my life?"